Gaming to Learn #01: Creating a Class Review Game from Bezier Games' America

In the Gaming to Learn article series, Jon discusses all aspects of board gaming from an educational perspective.

In the article “Board Games in the Classroom” in the Spring 2021 issue of Casual Game Insider, I mentioned that Terra, Concept, and Time’s Up are easily modifiable to use as class review activities. This spring, I took my own advice and made a review game based on Terra for my 10th grade English rhetoric class.

Terra (2014) is the second installment of a trivia game system designed by Friedemann Friese. Fauna (2008) was the first; in Fauna, players see a card depicting an animal and have to guess that animal's weight, length, height, and tail length. Friese’s innovation is that you don’t have to be exact to get points. Players place cubes on various scales depicting increments of these characteristics and get points if they are correct — but even if players have cubes adjacent to the right answers, they still receive some points. Players also place cubes on a world map divided into geographical areas, and the same rules apply: players get the most points for being correct and some points for being adjacent. This adds a fun tactical element to the game: if you are playing with someone who knows a lot about animals, you can place your cube on the spot adjacent to where they place their cubes and — assuming they are correct — still get some points.

Whereas Fauna’s trivia questions focused on animals, Terra’s are based on geography. Terra has a world map, too, as well as three linear scales (year, length/distance, number) on which to place cubes. Terra simplified the point system: for every cube placed on the correct answer, players receive 7 points, and for every cube placed on an adjacent space to the correct answer, players receive 3 points.

When I started to make my review game based on Terra’s system, I discovered that Ted Alspach from Bezier Games had further tweaked this system in America (2016), which focuses on Americana, such as how many pizzas are consumed each year in the U.S. Unlike Fauna and Terra, in America the three questions on the trivia cards each correspond to one of the three places on the board where players can place cubes: a map of the continental U.S. along with Alaska and Hawaii, a scale depicting years from 1492 to 2015, and a scale depicting numbers from 0 to 1 billion. Correct answers still receive 7 points and answers adjacent to the correct answer still receive 3 points. Also, for each of these three areas, two new spaces have been added, “No exact” which is worth 3 points and “No exact or adjacent” which is worth 7 points. These new spaces are good options if a player thinks the other players who have placed cubes in that area are way off.

America (photo courtesy Bezier Games)

Once I discovered America, I liked it immediately, and I decided to base my rhetoric review game on it. I made a prototype and tested it. Immediately I realized I needed to make some modifications. In America, each player gets 5 cubes to place each round, but they don’t have to place all of them. The reason players might want to do this is because they will lose every cube that they placed incorrectly (although players will get one wrongly placed cube back when the next round begins, and players always start with a minimum of three cubes no matter how many they got wrong the previous round). This system was too fiddly for my review game, so I just gave players 3 cubes to place every round. In further testing, I decided to give players only 2 cubes to place each round because there simply weren’t enough good spots for students to place cubes, especially when playing with 5 or 6 players.

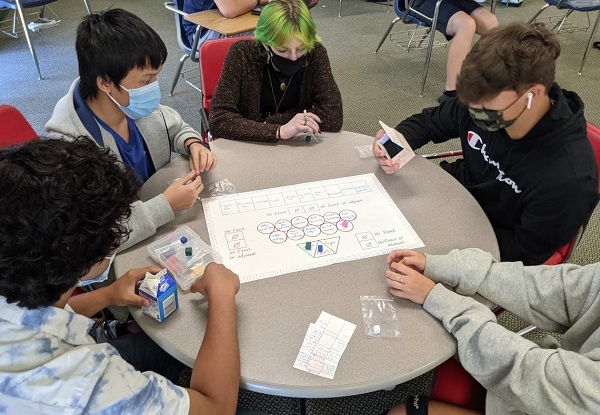

Finally, our class was ready to play! I split students into groups of five or six, and while the rest of the class did other review activities, each group took its turn to play. The five students in the class who got the highest scores during this first round would play a second time, and this time, depending on what place they finished in, they would receive a certain amount of extra credit points on the rhetoric exam.

For this final game, there were exactly five cards/rounds. This was extremely important because it would give each player exactly one chance to go first. Going first is a distinct advantage because if the starting player knows one of the answers, they can lock up that 7-point space before anyone else can grab it.

When one of the groups was playing their first game, one of the students loudly proclaimed, “This game is trash,” which, as you might imagine, was completely demoralizing. Upon reflection, I realized the student said this because this game was so different than anything they had played before. Based on America’s system, my review game was less a trivia game and more a euro game. To succeed in the game, what’s most important is not knowing the right answers but rather strategizing when and where to place cubes.

For the most part, though, students enjoyed the game. During the final game, when extra credit was on the line, the players were dead silent, to the point that the rest of the class wondered aloud, “What’s going on? Why aren’t you talking?” The players responded that they were deep in thought, thinking about the absolute best placement for their cubes. The “this game is trash” student had made it into this final game, and to my great satisfaction, enjoyed the competition immensely.

Silence during the intense competition of the final game

I learned that for students who are not used to euro games, simple rules are best. At the same time, I learned that there’s nothing wrong with introducing students to a new gaming experience outside their comfort zone. As students strategized where and when to place their cubes, they practiced the skill of critical thinking, which I would call a success! Furthermore, this review game accomplished the goal I had for it, which was to help students prepare for the rhetoric exam, but not in the way I expected. Instead of helping students review the material, it prompted students to reflect with comments like, “Wow, I don’t know logical fallacies as well as I thought I did. I need to study this before the exam!”