Learning and Teaching Games More Effectively

Games are a wonderful form of entertainment. They are far more social and interactive than many other forms of entertainment that we participate in. If we compare playing a game to going to the movies with friends, we see that both are very sociable activities, but with movies there is a large part of the middle where we don’t actually interact with our friends, but sit idly and watch the entertainment provided. With games, often for about the same monetary investment, we have social interaction throughout the event and provide our own entertainment.

However, games are not without their downside, and this downside relates specifically to the time investment of learning a new game. Once everyone knows how to play a game, then everyone can accept the time investment to play it, but it’s a big unknown when playing. How can one overcome this initial problem of time, and the difficulty of learning, and then teaching, a new game?

The first barrier to a new game is the rule book itself. It doesn’t really matter how well the rules are written; reading a rule book is not a lot of peoples’ idea of fun. However, there are some rare people out there who really enjoy reading the rules and thinking about how to apply them, and how they interact with each other. I happen to be one of these people, so much so that I am the game teacher among my friends and family.

The rule book also ruins one of the things that bring us the most joy: instant gratification. Going back to our movie analogy, I pay my five to ten dollars, then I am instantly rewarded with my entertainment. Games are not like this at all, because to first enjoy the game, we must know how to play. Our enjoyment of a movie has little to do with our understanding about how to make it.

Think back on the games you have learned. Unless you are one of the ones that really like reading the rules, then someone probably taught the game to you. This is one of the reasons Monopoly is so popular; everyone seems to know how to play. However, very few people have actually read the rule book. That’s why when you play with people that were outside your circle when you learned to play, there is often a lengthy discussion about how to play.

Commonly asked questions before a Monopoly game are, “do I put $50 or $500 in the middle of the board for the first person to land on Free Parking?” Or, “does the bank refill it or do just bank payments go there?” Often, these discussions are solved amicably, because rarely does anyone say, “let’s look in the rule book.” It’s probably for the better, since there is no rule that allows for this to occur.

This is not to say that the Free Parking rule, or any other house rule, is bad, but rather to point out that even one of the most purchased games in America doesn’t have its rule book read. And if we’re being honest, that’s fine since adult learners only retain 10% of what they read, anyway. So even if you are one of the few that read this rule book, you may not remember the rule that specifically discusses Free Parking, and that nothing special happens.

We can increase this retention to 20% through audio/visual methods, such as when a friend tells us how to play and maybe shows us some possible moves. Game companies are starting to post video tutorials to their websites in order to reach this higher level of retention and clarify the rules as written. These are a great way to learn the game, because you never have to think, “What did they mean by that rule?” These should be watched shortly before playing, since we soon forget most of what we do learn and retain if we don’t put it to use.

A demonstration will increase retention to 30%. For some, this may mean watching an entire game, which represents a significant jump in their time investment. And time investment is the barrier that we fight the most, and why this retention rate discussion is important. We must find a way to increase rule retention as quickly as possible, because most people won’t have fun at a game until they know and understand the rules behind it. The hard part about this is that people don’t even realize it’s one of the reasons they don’t have fun playing.

Many local game stores have demo copies of games available and are willing to teach you the game or show you a little about it. Some stores will even let you play a full demo game in the store. These stores are great and are my favorite to go to. Unfortunately, some stores don’t do a good job of letting customers know that they will do this. Part of this is economics; they need to sell games to operate, so they can’t have everyone coming in all the time to play games for free. If in doubt, don’t hesitate to ask if they can demo a game on the shelf, but do be respectful of their time when you do.

Practice brings the retention rate all the way up to 75%. This requires playing the game a little bit. With games like Rummy, it’s easy to play a practice hand or two before you start scoring for the game proper. Some other games won’t really “click” until you’ve played an entire game. Again, this can start to represent a large time investment. Many will be okay with this if it’s understood by all that everyone is trying to learn the game. If this isn’t clear, then it may be that someone expects to be competitive and have a great shot at winning, when the reality is that they don’t yet understand the rules enough. This is especially true if you are teaching a game that you are very familiar with.

But what is the #1 way to learn a game, with a 90% retention rate? Teaching the game to someone else! Now, the downside is that not everyone who plays will teach the game, but you can get closer to this by asking others to help with rules after the first game. I’ll often use this technique with friends when they come over and we are going to play a game they’ve played before. It’s easy enough to do: “I have to put the dinner dishes away, can you set up the game?”

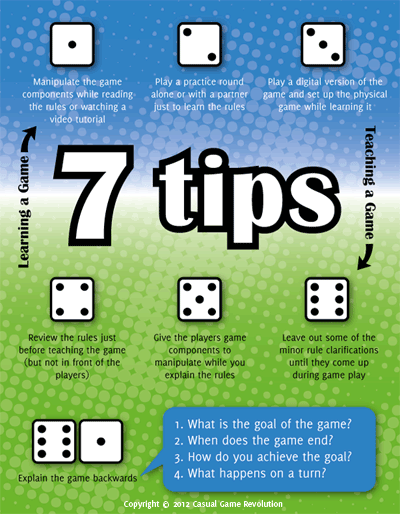

So, what is the best way to teach a game? First, you have to learn. If it’s a game that no one you know has played before, it probably means you’ll have to read the rule book or watch a video. Have the game out when you do this, and move the pieces around as if a game were going on. This will help your retention.

Refresh the rules just before you are to teach it. I have games that I’ve taught many, many times, and I still refresh just before we play again. However, be careful doing this with the group present. It’s OK to have the rule book handy when you teach the game, but long pauses to look up a rule or read it right from the book will often make others less excited to play the game.

When you teach the game, work backwards though the game. Start with the goal. For example: “The person who has collected the most sets of cards at the end of the game wins, and a set is four cards of the same value.”

Then explain the end game condition. “The game ends after everyone has dealt one hand.” Sometimes, this is combined with the goal of the game. For example, on a game with a board where everyone is trying to get to the last space, the goal is to get there first, and the game ends once someone gets there.

Then explain how the goal is achieved. How do you score points, or how to you advance your piece along the path? For example: “During each hand, once you have a set of four cards, play them to the table to count them.”

This is when you can explain what happens on a player’s turn. Sometimes this is combined with how to achieve the goal. “On your turn you will ask another player at the table for any cards that they hold of a certain rank. You must already have one of these cards in your hand. For example I could ask you for all of your Jacks as long as I hold one. Then the player will give you cards if they have them, or tell you to ‘go fish!’ if not. If you are told to ‘go fish!’ then you draw a card from the deck. If you got a match to the rank you asked for, either from the player you asked or from drawing the card, then you take another turn. Otherwise play passes to the person who told you to fish.”

In this case, we have another level of beginning and ending, and that is the hand itself. “The hand ends when the draw pile runs out, or a player runs out of cards in their hands. Deal passes to the left.”

This method of teaching eliminates the question of “what’s the point of the game?” Also, because you started with the goal, it will stay on everyone else’s mind throughout the game. As you teach the game, some may take little “mind breaks”. This is normal for adult learners, but everyone is focused at the beginning. Some will have questions as the game goes on, and that’s perfectly fine; it raises their retention level.

Before you start teaching, give everyone some game pieces. These serve as a good visual aid as you teach the game, but it also helps touch upon all three learning styles that exist. Some learn best by hearing, some learn best by seeing, and some need something tactile to play with to focus their mind. They fidget for a reason.

I hope this helps you enjoy games with your friends and family. Once you get past the initial time investment, you’ll find that you have a very rewarding social interaction that, when done often, has less financial investment than a trip to the movies.

What I believe to be superior is to devise a simplified, even simplistic version of the game, and start people playing within 1 minute of beginning the up-front lecture. Aim for just 30 seconds of up-front lecture. Get them participating ASAP, to start taking the cognitive load away and replacing it with familiarity. People don't want to learn, they want to play.

Then, after playing awhile (5 mins? 40 mins? You be the judge.), when you think everyone should have grasped what you've introduced so far, add another detail. For example, when I taught Stone Age, which has hard tiles and 2 kinds of flexible cards (grassy and sandy), I kept the 2 kinds of cards off the table, out of sight completely as if the game was complete without them, so they're not distracting and occupying any consciousness of the players, until someone had passed 50 points. Up to then, we were just dealing with tiles. Then I paused the game and taught how the sandy cards work. We played another 10 minutes and then I introduced the grassy cards.

As it so happens, none of the rules for Stone Age had to be changed by introducing the stuff in waves, they were all self-contained, but I didn't care about that. I want to stress that I never hesitate to completely throw away or change complex rules into simpler rules to get the game going and get people's arms moving their pieces, then upgrading the rules (and player options) at key points in the session, until people are playing the full shebang.

Is this perfect? No. Some players I've taught, no matter how many times they did the same basic thing, it never sunk in and they had to be told every time what to do, which got on the nerves of other players who were absorbing the rules easily. It's good to be prepared for that. Before teaching, ask yourself if it's at all possible to make up some player aids -- props they can hold or props they can look at, that show the rules in a way that's different from just the spoken presentation.

Every sense (sight, touch, hearing) that you can involve when teaching, the better. The few people for whom spoken rules don't click might just need to see a flowchart (perhaps with cutesy drawn pictures), to have that "aha" moment. It's worth the effort to make that diagram, so the game can run its smoothest and maximize the chance of everyone having a good time. When someone plays the whole session and never really "gets it", it detracts from the enjoyment of everyone.

These guidelines are good for games like Castle Panic or Survive... or Monopoly. What I find true is that I usually read the rules and play a mock game on my own a day or two before the game night. I give a few clues as to what to look for and how to do certain things then, in layman's terms. I find this helps a lot. I don't agree with the idea of 'leave out the minor details'. At least, in my group, there is always a feeling of "Oh, you didn't tell us that we could do [whatever]". This usually happens when *I* do something odd, that others did not realize you were allowed to do. Because of this phenomena, I tend to be extra careful to point out smaller rules.

That said, I do brush over some items in that - I summarize and move on - but I don't leave out completely.

I do agree with talking through the game backwards. That's often what I do too. "The basic concept is XXX..." then I tell them how to win, and so on...

My method of playing games on my own means that it's a little funny looking in the game room with a new set-up and I move from seat-to-seat-to-seat and play as if I am each person. :) Oh well, it gets the job done.